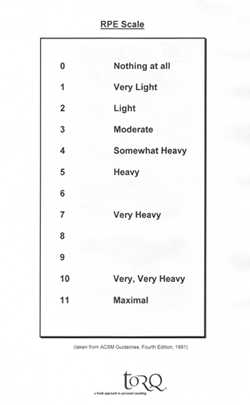

For the unaware, the Borg Scale has been used in exercise physiology laboratories and by coaches for years to assess an athlete’s level of exertion whilst they’re exercising. The Borg Scale is often referred to as RPE (Rating of Perceived Exertion) and is entirely subjective. Quite simply, when an athlete is being tested in a laboratory setting, they are asked to pinpoint how hard they feel they are working by giving the examiner a rating from a chart that is presented before them. The original Borg Scale has 21 points of exertion ranging from 0 (at rest) to 21 (maximal). These were adapted later on to produce a 15-point scale called the ‘category scale’, strangely ranging from 6 to 20 and the ‘category-ratio scale’ ranging from 0-10. The later scale has a point beyond 10, which is deemed ‘maximal’, really giving it 11 points (see picture below).

I’ve always been a massive fan of assessing exertion in this way, because it bypasses many of the errors that modern tools like heart rate monitors tend to throw up. If you speak to a TORQ rider, they’ll all have an RPE scale, the contents of which will have been drummed into them mercilessly time and time again by yours truly. Why? Because it works! RPE, if fully understood, can be used to prescribe very precise training levels and once the athlete fully understands it, they really are at one with their body and this is vital for peak performance in any aerobic discipline.

A heart rate monitor is a useful tool for steady-state aerobic work, there’s no doubt about it, but it can’t be totally relied upon or you’ll become an ignorant slave to it. If it’s a cold day, your HR is lower and the same if you’ve not recovered properly from your last training session. If you’re dehydrated it’s higher and the same if you’re hot or over-dressed. Caffeine elevates HR too and did you know that for a given intensity your HR will drift upwards more and more the longer you ride for?

The mismatch between RPE and HR has been confirmed in a recent review in the Journal of Sports Sciences, Issue 20 (2002). There’s also a good summary of the paper in the Peak Performance Newsletter Issue 177 (2003). Furthermore, the research shows that RPE correlates very well with a variety of more reliable indicators of exercise intensity such as blood lactate, VO2, ventilation and respiration rates. This confirms to me that understanding and ‘feeling’ your way through training is likely to harvest far more positive results than simply slapping a HR belt round your chest and training at what can often be inappropriate intensity levels.

This said, ultimately you’ve got to look at the big picture and a HR monitor can help if used appropriately, but not exclusively. Look out for power measuring technology when you’re next shopping for gizmos, because these really do provide useful feedback. Many of the TORQ riders have been using power and wattage very successfully this winter and using RPE, HR and power together provide a very ‘real’ profile of the rider.