If you’re going on a long journey in the car, you have to make sure your fuel tank is topped up before you leave. The more fuel you have in the tank, the longer your range will be. This concept is exactly the same with exercise, instead the fuel we add to the body is carbohydrate from the food we eat.

We have written a short article on Carbohydrate Loading previously, to provide a background and some general advice, however on this occasion we discuss the research history (it goes back as far as the 1960s) and provide you with the best possible up-to-date advice on how to Carbohydrate Load for the best endurance performances.

In endurance races, all else being equal, the person who can maintain the highest pace for the longest period of time will win. Of course, there are a whole variety of ways that we can try to maximise our training effectiveness in the months leading up to our key events so that we are at our fittest when the big day finally arrives. We have recently written a series of articles on Periodisation & Peaking, so if you are interested in learning more about how to train your endurance engine, please take the time to give them a read:

Independently of fitness however, your nutritional strategy will literally make or break your endurance performance. It doesn’t matter how fit you are, if you get your nutrition wrong, you could be beaten by people significantly less fit than you who have got it right! There’s another way of looking at this – a well planned nutritional strategy can also mask shortfalls in fitness. Carbohydrate Loading is one such strategy and that’s what we’re going to discuss here.

Which Fuels Does Our Body Use During Exercise?

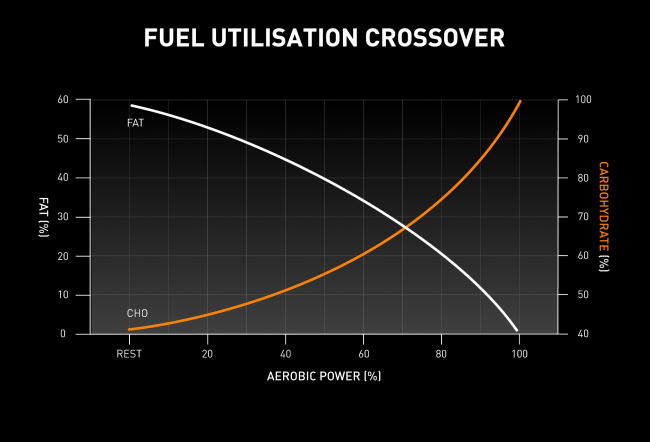

During exercise our body relies on two fundamental fuel sources, fat and carbohydrate. We also burn a little bit of protein, but this only becomes significant in the absence of available carbohydrate and hopefully after you’ve read this article, running low on carbohydrate is not something that’s going to happen to you! The reliance on fat and carbohydrate changes with exercise intensity and fuel availability. At a low exercise intensities, fat offers a large proportion of the fuel we use for energy production and as exercise intensity increases, we see a significant shift towards carbohydrate as the preferred fuel source.

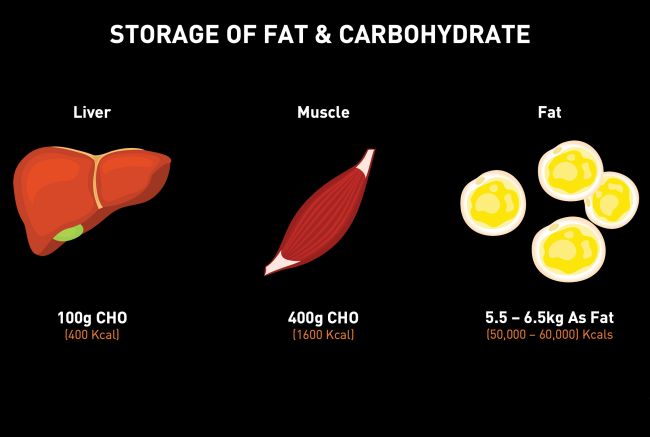

There are some significant differences between fat and carbohydrate with the quantities in which they are stored in the human body. Fat is theoretically ‘limitless.’ Even the fittest and leanest of us could still be carrying in excess of 50-60,000 calories worth of fuel, so even the longest of exercise sessions will not so much as a dent into our stores of fat. It’s a very different story with carbohydrate on the other hand. Carbohydrate is stored as the molecule glycogen in two main sites, the muscle (400g worth) and the liver (100g worth) with a total capacity of around 500g, equivalent to 2000 Kcals. When we compare the storage capacity of fat and carbohydrate in the human body, it’s easy to see how our carbohydrate stores can be quickly depleted as the reservoir is significantly smaller.

Research has suggested that when we work at our maximal sustainable intensity, carbohydrate breakdown (oxidation) rates can peak at ~3g/min equating to 180g of carbohydrate being burnt in 1 hour. At these rates, carbohydrate stores could be depleted to critically low levels in as little as 2.5 hours. This would also assume that you started your exercise session with fully saturated muscle and liver glycogen, which many of us won’t have, further reducing our time to exhaustion. Also, many endurance events involve intermittent bursts of pace (sprinting/hill-climbing), which deplete carbohydrate reserves significantly faster, so stores could become fully depleted in as little as 1.5 hours.

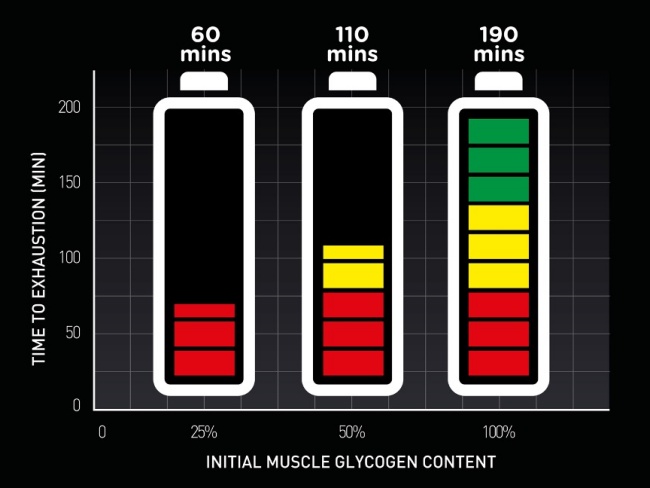

One of the very first performance-based studies exploring the effect of muscle glycogen on performance was from Hermansen and colleagues (1967), who found that initial starting muscle glycogen content plays a significant role in increasing time to exhaustion when exercising at 75% of VO2max. Time to exhaustion is a phrase commonly used in the Sports Science community to describe ‘lasting longer’ or ‘extending endurance.’ To you and I, 75% of VO2max would be considered a moderate to hard exercise intensity, depending on how fit you are. Hermansen and colleagues (1967) found that when participants consumed an energy-matched diet (meaning the number of calories within all diets were the same between subjects), but the percentage of carbohydrate within the diet were altered between 3 different conditions at 5%, 52% and 82%, time to exhaustion significantly increased from 2 hours in the 5% trial to 3.5 hours with the 82% carbohydrate trial.

Methods of Glycogen Loading

When we explore the approaches used to replenish carbohydrate post exercise, there is one key enzyme that we need to keep in mind called ‘glycogen synthase’. Very simply, this enzyme is the tool responsible for converting carbohydrate that we eat in to the stored glycogen found in the muscle and liver. The greater we can stimulate glycogen synthase, the more likely we are to saturate our glycogen reservoirs. Below we will look at some of the classical and more modern approaches to stimulating this key enzyme.

Classic Approach: Early glycogen loading regimes required a very focused and strict dietary approach. Work from Ahlborg et al., (1967) found that after a bout of exercise designed to deplete muscle glycogen, followed by a high carbohydrate diet consisting of 90% of the daily calories from carbohydrate for three days, muscle glycogen was replenished to moderate values. Whilst this showed that this protocol was effective in replenishing glycogen, the modest result was unsatisfactory. The study was repeated, and in the subsequent trials, once participants had depleted muscle glycogen, they consumed a very low carbohydrate, high fat, high protein diet for 1 and 3 days respectively before consuming the same 90% carbohydrate for 3 days.

The results showed that when participants kept carbohydrate low for 3 days after the glycogen depleting exercise bout, muscle glycogen replenishment over the 3 days achieved almost maximal saturation values. The 3-day, low carbohydrate diet resulted in the enzyme glycogen synthase becoming highly active as it tried to scavenge for the limited carbohydrate in the low carb diet to store as glycogen. Of course, once carbohydrate was reintroduced at higher rates, the highly active enzymes became saturated in carbohydrate and an abundance of glycogen was stored.

Classical Approach Limitations: Whilst this loading strategy was highly effective, there are certainly a number of practical limitations that could affect your preparation in the lead up to a major event. In our recent Peaking for Competition article, we discussed the importance of maintaining exercise intensity in the lead up to any major event whilst reducing exercise volume. As with any high intensity effort, carbohydrate provides the majority of the fuel and so if these efforts are completed during the low carbohydrate phase, your physical preparation will be compromised.

Low energy availability in the form of a low carbohydrate diet can also have a significant impact on mood and motivation. The brain solely uses carbohydrate as a fuel, so if you purposely restrict carbohydrate, it’s hardly surprising that you could see a dramatic change in mood. As you prepare for a major event, it would certainly be advantageous to be in a confident, positive and happy state of mind as psychology plays a major role in sporting performance.

Lastly, whilst overall exercise may support the immune system, high intensity exercise combined with a low carbohydrate diet could suppress the normal function of the immune system. It really doesn’t seem logical to increase your risk of illness and infection in the days leading up to a major event because of a low carbohydrate diet. To understand more about exercise and nutrition and how to support your immune system, read our Immune System Support resources by clicking HERE.

Modern Carbohydrate Loading Approaches: In the early 2000’s, research started to explore new strategies of glycogen loading which would aim to remove the complexity and potentially disruptive nature of the carbohydrate depletion phase, whilst still optimising glycogen storage. A potential benefit to this new approach would result in a significantly reduced glycogen loading duration, resulting in far less disruption as you count down the days to your event. Vanessa et al., 2002 asked participants to consume a very high carbohydrate diet, consisting of a 10g/kg (700g for a 70kg athlete) for 72 hours, and muscle glycogen samples were analysed at 24 hours and 72 hours. The results were somewhat staggering, as this study was the first to show that within 24 hours, muscle glycogen content can be increased by 90% after a single day of consuming a high carbohydrate diet (10g/kg).

There is one ‘applied’ question left unanswered by this study however. Whilst carbohydrate loading is very important in ensuring there is plenty of fuel available to perform at your best, completing no activity at all (the approach used in the above study) in the run up to a major event is certainly not advisable as research into training and conditioning has suggested that just a few days of inactivity is enough to reduce optimal physical performance. So, whilst this study showed us what is possible and was far less restrictive than the classical approach, it still struggled to fully address the real world application to racing and competition, where it is typically advised to complete high intensity, low volume training in the days running up to a major competition or event.

This brings us nicely on to the next study. Fairchild and Colleagues (2002), a group from the University of Western Australia, helped to answer these applied questions. Their research saw participants warm up for 5 minutes and follow this with an exhaustive 3-minute exercise interval. The participants then followed a high carbohydrate diet consisting of 12g/kg (840g for a 70kg person) for the next 24 hours. The results confirmed those of Venessa et al.,(2002) which demonstrated very high levels of glycogen storage within the following 24 hours. In addition, the 3-minute exhaustive high intensity bout of exercise would serve as the perfect pre-event primer.

The mechanisms allowing this protocol to be highly effective are rather complex so we will just cover the foundations. When we exercise, glucose transport molecules responsible for transporting glucose from the bloodstream to the muscle (a transporter known as GLUT-4) become highly active and move from the centre of the cell to the cell border where they can pick up glucose and draw it back into the muscle for it to be used for fuel. GLUT-4 is activated very quickly by muscular contraction (seconds), but the rate of deactivation is much slower. When the 3-minute exercise bout is finished, the glucose transporters remain highly active for around 20 minutes and a very large dose of carbohydrate taken immediately afterwards is drawn swiftly into the muscle cells. As exercise has finished, the carbohydrate can’t be used as a fuel, so the only other option for it is to be stored as glycogen, kick starting the loading process.

TORQ Recovery Drink is the perfect ‘large dose’ of carbohydrate to consume at this stage, because it contains what are called ‘multiple-transportable carbohydrates’ providing the high glycaemic index (GI) carbohydrates to support the above process as well as lower GI fructose, which is quickly and simultaneously absorbed into the blood and directed straight to the liver for storage. One drink that addresses both muscle and liver glycogen. The addition of protein within TORQ Recovery Drink also provides material for muscular repair and maintenance and has been shown to increase circulating insulin levels – another tool to assist in the storage of carbohydrate.

Carbohydrate Loading: Some Basic Rules

Carbohydrate loading is not as simple as just eating more food and it is certainly not an excuse to go out and binge on whatever food sources you deem suitable. Instead, we do have to be a little more calculated with our approach.

Don’t Just Eat More: Whilst it is important to increase the amount of carbohydrates consumed within the diet during a carbohydrate loading phase, we should still aim to achieve a similar daily calorie target and avoid over consumption. You should look at your daily energy intake and consider where these calories typically come from. For most of us participating in endurance sport, we would consume what is known as a mixed diet consisting of around 50-55% carbohydrate, 20-25% protein, and 20-30% fat per day. During a carbohydrate loading phase, we would aim to achieve 70-80% of carbohydrate whilst maintaining 15-20% protein (we mention the importance of maintaining protein intake at the end of this article). This doesn’t leave much of a percentage for fat – so minimal fat intake is key for a successful carb loading campaign.

As an example, for a 70kg person within a high load training phase, a 3500 Kcal daily calorie target would certainly be deemed reasonable to maintain body mass. During the carbohydrate loading phase, targeting 75% of these calories from carbohydrate would result in 2800 Kcals from carbohydrate, equating to a total of 700g of carbohydrate for the day. In relative terms, this would work out to be 10/kg of carbohydrate/kg of body weight per day, perfectly achieving the text book target.

Stay Hydrated: Ensuring there is plenty of water available during a glycogen loading phase is critical. Water is required in the formation and retention of muscle glycogen. Research has demonstrated that the ratio between glycogen to water is 3:1, so for every gram of carbohydrate stored, 3 grams of water are required. This is why being slightly heavier after a glycogen loading phase is a good thing. If 500g of carbohydrate can be stored between the muscle and the liver and 3g of water is required for every gram, you should find yourself between 1.5kg and 2kg heavier come the morning of your major event. Many high carbohydrate foods like rice and pasta have water absorbed into them after cooking, so the carbohydrate/water balance will take care of itself, but it’s vital that you drink plenty when consuming drier more concentrated forms of carbohydrate like bread and sugary snacks.

Types of Carbohydrate: We could talk to you about Glycaemic Index (GI), which is the speed at which the carbohydrate gets from food into your blood, but ultimately your aim is to hit the high carbohydrate intake targets we’ve spoken about. It used to be that people thought that complex starchy carbohydrates gave a low GI and sweet sugary things have a high GI, but it’s more complex than that. For instance, fructose (fruit sugar, which is 3 times sweeter than table sugar) has a very low GI (around 25) and a baked potato, which is full of complex carbohydrate has a high GI (around 85). The bottom line is that the GI of foods is not a factor here and it actually comes down to the density of the carbohydrate calories and their ease of consumption. Sugary snacks like sweets/confectionary are densely packed with calories and are also low in fat, so are ideal for carbohydrate loading with. Pasta, rice and potatoes carry more fibre and other nutrients and their bulky nature can stop you hitting your high carbohydrate targets. The key to successful carbohydrate loading is to consume a mix of all sorts of carbohydrate, but for 24 hours prior to your event, don’t get too hung up on ‘health’ as such – you’re going to need to eat some things you might not normally indulge in!

High Carbohydrate Foods: As we alluded to above, traditional complex carbohydrate foods like rice, pasta, bread, potatoes and beans/legumes should continue to feature in your carbohydrate loading diet. The difference perhaps to a normal day would be the addition of high carbohydrate, low fat snacks like jelly babies, wine gums, flavoured rice cakes (sweet or savoury available), Scotch pancakes and Chelsea buns. The last two are slightly higher in fat, but they are sufficiently low not to qualify as cakes or biscuits, which you should avoid.

Other than the suggestions above, funnily enough TORQ has an entire online store full of high carbohydrate, low fat foods and drinks which can be considered as part of the carbohydrate loading process. Our TORQ Energy Bars for instance represent some of the lowest fat, highest % carbohydrate energy foods on the market today. Our Explore Flapjacks could be used in moderation, but whilst being half the fat of a regular flapjack, they do carry significantly more fat than a TORQ Energy Bar. They’re probably in Scotch pancake territory!

We have already mentioned the use of TORQ Recovery Drink immediately following your 3-minute intensive exercise bout, but also consider how TORQ Energy Drink can be used to ingest more carbohydrate whilst simultaneously hydrating. An energy drink provides carbohydrate and fluid to support the carbohydrate loading process, plus it’s very easy to consume and contains zero fat.

There is one product we produce however, which has literally been made for carbohydrate loading and that is TORQ Energy Organic.

Beyond functioning as a flavourless energy drink, this product has many more uses. Often dubbed ‘the invisible calorie’ by our customers and performance coaches, TORQ Energy Organic is the ideal product for increasing carbohydrate intake at times when the body is under high training stress or you need to carbohydrate load to peak for an event. Sometimes it’s simply impossible to consume the amount of carbohydrate calories required and TORQ Energy Organic makes this challenge so much easer. This can be achieved in a variety of ways:

Create a Rich Energy Drink: Because TORQ Energy Organic is practically flavourless, it’s possible to mix up a very concentrated energy drink and add a little juice concentrate (squash) to flavour it if desired, or you can mix it with our regular flavoured TORQ Energy Drink to make it more concentrated. TORQ Energy Organic has the density of sugar, but nowhere near the sweetness or osmolality in the gut, making high concentrations of carbohydrate easy to handle.

Add to Tea, Coffee or Soup: Again, the flavourless nature of TORQ Energy Organic delivers a very high level of versatility. Significant amounts of powder can be added to tea, coffee and soups with a barely recognisable effect on flavour. With soups, TORQ Energy Organic can actually lift the flavour and add extra thickness/body.

Add to Sauces, Porridge or Custard: At TORQ, we call it ‘Bionic Custard’ because regular custard is pretty high in carbohydrate anyway, but add a few scoops of TORQ Energy Organic to your portion and it’ll taste even better and improve the texture. Similarly, this powder can be added to savoury sauces that you would usually have with rice or pasta, where the product truly lives up to its ‘invisible calorie’ reputation.

Add to any Sweet or Savoury Recipe: Whether you’re making cakes, flapjacks or pancakes, there’s always room to squeeze in some extra energy. Simply add some TORQ Energy Organic to the recipe – no need to alter it and with a bit of practice you’ll be able to fine-tune the right amount.

Sprinkle on Anything: Whether it’s your breakfast cereal or a curry, the limit is in your imagination!

So, if you’re thinking of purchasing, a specialist Carbohydrate Loading product, this is the one.

The Pre-Event Breakfast: Your pre-event breakfast should be consumed around 3-4 hours before the start of your event. Once carbohydrate enters the muscle and is stored as fuel, it will remain there until it is used. Liver glycogen on the other hand is used to keep us alive, ensuring that blood glucose remains in adequate ranges. This means that the liver will slowly drip feed carbohydrate into the blood constantly through the day, providing your brain and major organs with fuel. The liver plays a vital role during the night in maintaining blood glucose as we fast whilst asleep. Come the morning of your event it is possible that we could see a significant depletion of liver glycogen and so the role of the pre-race breakfast is to replenish liver glycogen, rather than muscle glycogen stores.

Your pre-race breakfast should contain a mix of high and low GI sources, delivering an overall moderate GI to avoid spikes in blood glucose and you should aim to consume around 1 – 2g/kg of carbohydrate. Some research has recommended up to 3g/kg of carbohydrate pre breakfast. For a 70kg individual this would be 210g of carbohydrate which would be considered very high, especially on that nervous pre-race stomach that we often face before a race or major event. Our advice would be to target between 1-2g/kg of carbohydrate for your pre-event breakfast based on personal tolerance. We really don’t want to be putting any unnecessary stress on the digestive system before your event and if you have carbohydrate loaded properly the previous day, this will be plenty.

Our 5:1 Carbo-Load Breakfast takes the stress out of perfecting your pre-event breakfast. This breakfast packs a punch by delivering 125g of carbohydrate and 25g of protein. For most body weights, this ratio fits perfectly within the 1-2g/kg.

Protein

As we’ve been rattling on about carbohydrate for so long, you’d be right in noticing that we’ve paid little attention to protein in this article. This is partly because we have already addressed protein thoroughly in the following article:

Protein, Performance and 20-25g Protein Recipes

That said, we should repeat that it is ‘fat’ that is sacrificed on the altar of carbohydrate loading and that it is vital to ensure that you still maintain protein consumption to the tune of 20-25g every 4 or 5 hours to maintain muscle integrity along with keeping bodily organs and enzymes happy. This is why we include 25g of Protein in our 5:1 Carb-Load breakfast, ensuring that you get this vital high quality protein into your system during the first meal of the day.

Do I Still Need To Fuel?

Whilst Carbohydrate Loading has been proven beyond doubt to extend time to exhaustion, there is still a limit to the amount of carbohydrate the body can store. This means that Carbohydrate Loading alone will not be enough to stave off fatigue, particularly during prolonged endurance events and those requiring a sustained high intensity. Therefore, fuelling with exogenous carbohydrate (food and drink like energy drinks, energy gels, energy bars and energy chews) will also need to be part of your strategy. As we said at the opening of this article, getting your nutritional strategy right, by Carbohydrate Loading in combination with fuelling properly will give you a distinct advantage over the competition. To learn more about fuelling, visit our Fuelling System page by clicking HERE. Also take a few minutes to watch this video, which explains the interplay between stored (endogenous) carbohydrate and external (exogenous) carbohydrate:

Conclusion

Carbohydrate Loading is an important protocol to consider ahead of any major endurance event within your calendar. Ensuring that your muscle and liver glycogen stores are fully saturated with fuel will allow you to maintain your pace for longer and deliver your best possible performance. The correct method/protocol for Carbohydrate Loading is commonly overlooked and many people think they’re doing it properly yet are often under-consuming or compromising their physical preparation by ceasing exercise in the days before an event. We would highly recommended following the Fairchild et al (2002) 1-day protocol as this has shown to be far less disruptive to your tapering schedule whilst still offering all of the benefits of a traditional 6-day protocol. Incorporating an all-out 3-minute effort including a warm-up and cool down will help to maximise glycogen storage if immediately followed by a Recovery Drink and a high carbohydrate diet targeting 10-12g/kg bodyweight is consumed for the next 24 hours. A high carbohydrate breakfast containing 1-2g per Kg bodyweight 3-4 hours prior to your event will replenish your liver glycogen stores, which will have depleted significantly whilst sleeping. You are reminded not to ignore regular 20-25g protein feeds during the 24-hour Carbohydrate Loading process. Finally, whilst Carbohydrate Loading will extend time to exhaustion, it is not a substitute for fuelling during exercise with exogenous carbohydrate sources.

If you have any questions about this article or any other subject, please don’t hesitate in contacting us at enquiries@torqfitness.co.uk or phone 0344 332 0852. Please note that we also have a Fitness Consultancy if you would like to discuss any of the areas of this article in deeper detail. Click HERE for further information on our services.

References:

Hermansen, L., Hultman, E. and Saltin, B., 1967. Muscle glycogen during prolonged severe exercise. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 71(2‐3), pp.129-139.

Fernández-Elías, V.E., Ortega, J.F., Nelson, R.K. and Mora-Rodriguez, R., 2015. Relationship between muscle water and glycogen recovery after prolonged exercise in the heat in humans. European journal of applied physiology, 115(9), pp.1919-1926.

Ahlborg, B., Bergström, J., Ekelund, L.G. and Hultman, E., 1967. Muscle glycogen and muscle electrolytes during prolonged physical exercise1. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 70(2), pp.129-142.

Wilson, G., Drust, B., Morton, J.P. and Close, G.L., 2014. Weight-making strategies in professional jockeys: implications for physical and mental health and well-being. Sports medicine, 44(6), pp.785-796.

Cordain, L., Eades, M.R. and Eades, M.D., 2003. Hyperinsulinemic diseases of civilization: more than just Syndrome X. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology, 136(1), pp.95-112.

Sedlock, D.A., 2008. The latest on carbohydrate loading: a practical approach. Current sports medicine reports, 7(4), pp.209-213.

Fairchild, T.J., Fletcher, S.T.E.V.E., Steele, P.E.T.E.R., Goodman, C., Dawson, B. and Fournier, P.A., 2002. Rapid carbohydrate loading after a short bout of near maximal-intensity exercise. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 34(6), pp.980-986.

Bussau, V.A., Fairchild, T.J., Rao, A., Steele, P. and Fournier, P.A., 2002. Carbohydrate loading in human muscle: an improved 1 day protocol. European journal of applied physiology, 87(3), pp.290-295.

Hargreaves, M., Costill, D.L., Fink, W.J., King, D.S. and Fielding, R.A., 1987. Effect of pre-exercise carbohydrate feedings on endurance cycling performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 19(1), pp.33-6.