We conclude our 3-part series on periodisation and peaking with the exciting topic of peaking your form so that you perform optimally at the important events you have planned for the season.

Having explored the concepts of the Off Season in our first article, swiftly followed by a guide to Planning Your Training, we now focus on the final part of the perfect endurance preparation puzzle, which is to capitalise on all the hard work you’ve put in over the autumn and winter months. We walk you through how to bring your best performance to the start line and provide you with practical tips to ensure that you ‘peak’ correctly, based on years of scientifically supported evidence.

Understanding The Lingo

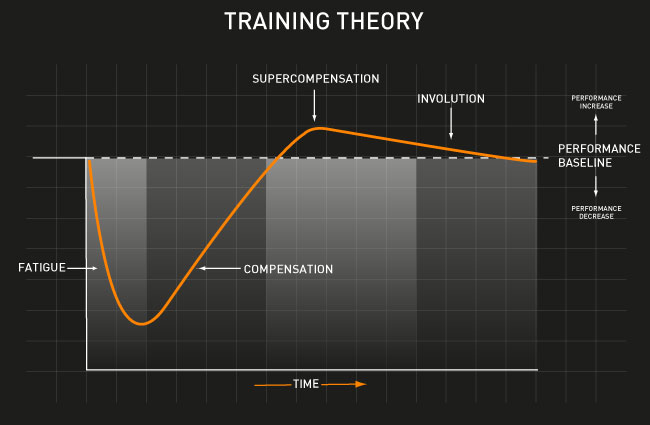

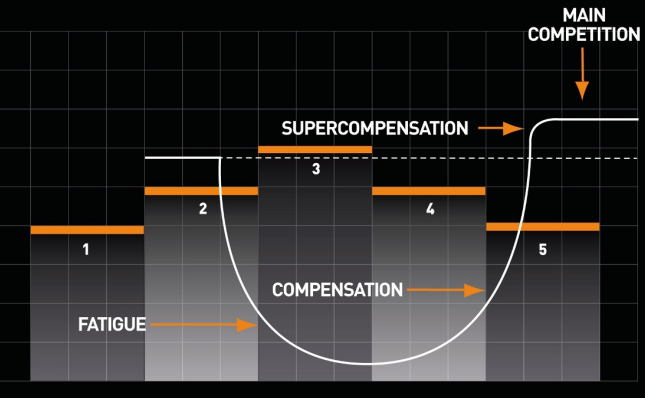

In our second Periodisation & Peaking article Planning Your Training we looked at various frameworks used to maximise training effectiveness. We explored how an improvement in fitness is driven by a fatigue stimulus (exercise/training) followed by a recovery phase. This recovery period allows the human body to compensate and a period of ‘Supercompensation’ then follows which is essentially a window of over-recovery, generating a higher level of fitness, or peak in form.

Throughout this article we will be focusing on two main phases of the training model noted above. The first being Compensation which we will refer to as the ‘taper phase’ and the second being Supercompensation which we will refer to as the ‘peak.’ The concept of tapering and peaking can be defined as:

‘A progressive reduction in training load over a planned period to reduce physical and psychological stress resulting in a peak in exercise performance.’

This is a definition supported by the trajectory of the performance curve seen below. The principles exhibited in the Training Theory diary above apply here too, it’s simply that the principles of fatigue, compensation and supercompensation are applied over a longer timescale (weeks rather than a single exercise session).

Science Or Art?

We can determine an exercise taper as a cause and the peak in performance as an effect, yet without speaking in too many riddles, the process of tapering is commonly referred to as an art rather than a science. This is because to reach a performance peak, you must taper your training as you move closer to your event, yet years of research in these areas has highlighted an exceptionally large inter-individual variation in response to the perfect taper. Therefore you will need to understand the principles involved so that you can fine-tune the perfect taper for yourself.

What works for one person may not be as effective for another, even if the training and event targets have been similar between two people. Research in this area has covered a whole variety of different endurance sports and have compared a wide variety of tapers, highlighting those delivering the best results. We explore the research and bring you some conclusions below.

Aims Of A Taper

By the time you arrive at the taper phase (typically 1-2 weeks before your target event, but we discuss this in detail further down), you should not be looking to generate any more training stress. Instead, you should be starting to reduce your training load. Training load is regulated by three fitness variables:

Volume: The amount of training hours per week.

Intensity: How hard the training session is.

Frequency: How many times you train each week.

Any training in the hunt for further adaptations within the taper phase will simply limit the recovery process and you increase the risk of carrying unwanted fatigue into your event. The taper must allow you to maximise recovery via a reduced training load, yet limit the amount of detraining (loss of fitness). As we established from the previous article, exercise sessions focused on strength and power are quickly trainable, but they also detrain quickly. It’s these types of powerful efforts however that provide you with the winning edge over the competition so the timing and structure of this taper is critical.

Reducing The Training Volume

It is well reported that a high training volume will promote a greater degree of physiological stress than a hard but short interval session. The highly depleting, degrading, and continuous nature of prolonged exercise is fatiguing from a physiological (cellular), biomechanical (structural), neural and psychological perspective and so this is certainly one of the first training variables to reduce in the attempt to clear the fog of fatigue.

Mujika and colleagues (2000) explored the effects of a 50% reduction or 75% reduction of training volume during a 6-day taper phase in well trained runners. The result confirmed that the group who reduced their pre-competition training volume by 75% proved have be a more appropriate strategy. Investigations have established increases in total blood volume, red blood cell count and increased haemoglobin (the oxygen carrier within the red blood cells) as a result of a taper. As the oxygen carrying capacity of the red blood cell is increased, along with a total volume of red blood cells carrying oxygen to the muscle, it is easy to see that endurance exercise could be enhanced through a correctly timed taper.

Some studies have even reported a huge (up to) 90% reduction in training volume during a progressive 3-week taper phase. We would not typically recommend a reduction of this magnitude unless you have been exposed to an intense/excessive training load in the weeks leading up to an event and there is a substantial amount of fatigue to clear.

A meta-analysis from 2007 conducted by Bosquet and colleagues explored 27 different studies and highlighted that the greatest impacts on performance were noted after a 41–60% decrease in total training volume during the taper period. With this in mind, we would recommend that you experiment with reducing your training volume by up to 60% and certainly no less than 40%.

Reduction Of Training Intensity

Whilst it may seem logical that hard training intensities can generate an unwanted trough of fatigue, as explained above, it is often the longer endurance focused training sessions that generate lingering fatigue. Hickson et al., (1985) established that after 10 weeks of intensive endurance training, the performance gained throughout this training period could not be maintained in the following 15-week period when the training intensity was reduced, even though training volume and frequency remained the same. This highlighted that short and sharp training sessions can elicit just enough training response to maintain the adaptations to training without inducing a training stress/fatigue response. Remember, it is important that you do not fall into the trap of detraining during a taper, as it’s vital that you maintain your ability to perform. The only alteration should be to clear residual fatigue.

Having a high maximal aerobic power (the ability to efficiently produce power through the aerobic energy system) is inevitably one of the greatest determinants of endurance sports performance. Developing the aerobic engine allows you to become more efficient, meaning less oxygen is required to complete a set task, alters & improves the fuel selection (fat or carbohydrates) at different exercise intensities, improves oxygen delivery and improves the muscles’ ability to extract oxygen from the blood for utilisation. Research has suggested that simply a few days of inactivity is enough to reduce total blood volume, the activity of enzymes responsible for aerobic power development and the reduction of enzymes responsible for storing muscular carbohydrate (glycogen).

All of these factors have the capacity to limit maximal aerobic power, so we would suggest adding some VO2 max style efforts into your taper to keep the aerobic engine firing optimally. These sessions look to accumulate between 10 minutes of ‘time in zone’ (the amount of time you are working within your VO2max power or heart rate range) with the interval duration will last commonly between 1 minute 30 seconds and 5 minutes. As you are not looking to provide an adaptation response to your training within the taper phase, you will want to focus on keeping the work:rest ratio at 1:1, which would mean that the work interval time is the same as the recovery time. As an example, 10 minutes ‘in zone’ could include 5 X 2-minute intervals with 2 minutes recovery between each interval. These sessions could be used to replace some of your longer endurance sessions.

If your training program usually contains some shorter anaerobic intervals, you should also continue to maintain these within your taper also.

Reduction Of Training Frequency

Training frequency refers to the total number of sessions completed within the taper phase (how frequently you train). Research has suggested that adding more rest days as a method to reduce total training volume does not provide a significant performance advantage and may even limit event performance by allowing detraining to occur. Research suggests that the training frequency should be maintained at around 80% of the pre-taper levels. Maintaining the frequency of training becomes even more important to sports which require a greater skill/technical component. Sports such a mountain biking, swimming, racket sports and team sports could alternate training days between intensity days and skill-based days to maintain the training frequency. This would ensure that the sport-specific skills are kept sharp.

Optimising Taper Duration

Choosing how long the taper period needs to be is one of the most difficult choices you will need to make, as you will need to try to maximise recovery whilst limiting detraining. The exact timeframe between a successful taper and the negative implications of insufficient training is unfortunately not fully understood. This is because the extent of the pre-taper training load can play a significant role in the time needed to clear the training-induced fatigue and this means that there is a huge discrepancy between individuals and individual situations. However, a meta-analysis from the American College of Sports Medicine correlated different taper durations with optimal performance from a magnitude of different research summaries and concluded that a taper period of 8-14 days is deemed optimal. It stands to reason that if you enter the taper phase in an extremely fatigued state after a stint of very high load training, your taper period should be longer – closer to 14 days. If you are less fatigued going into the taper period, you would benefit from a shorter taper.

The Day Before Your Event

You may be tempted to rest-up the day before your event to save your energy so that you can explode into action 24-hours later. If not to rest up, perhaps a little bit of gentle exercise to keep the limbs ticking over? Research suggests that the last thing you should be doing is nothing or ‘going slow’ the day before an event and that you should conduct a short sharp interval session the day before competition. This session should not be protracted enough to induce fatigue, but instead should leave the muscles and nervous system primed for action so that the last thing your body remembers is speed! In Mountain Biking, competitors often do what’s called a ‘hot lap’ at race pace the day before competition for this reason. 1 lap is a fraction of the distance they will actually be racing, but the intensity of the effort primes them for action.

Nutrition Within The Taper

Within the taper period, calorie expenditure reduces along with training load, so you should find yourself less hungry than normal and you shouldn’t have to ‘try’ too hard from a nutrition perspective. Maintaining a regular frequent protein intake is essential in preserving the hard-gained muscle mass you’ve worked for as well as supporting your body’s biochemistry. Please take the time to read our comprehensive article on Protein so that you fully understand this topic area.

For many sporting events, the nature of the exercise within the taper and a healthy diet should be sufficient to maintain good levels of carbohydrate within the muscles and liver, but for high intensity endurance events, particularly if they are prolonged in nature, you should look to increase your carbohydrate intake 48-72 hours before the event. Following a dedicated carbohydrate loading regimen like the one we have discussed here could also pay dividends for extreme events of this nature

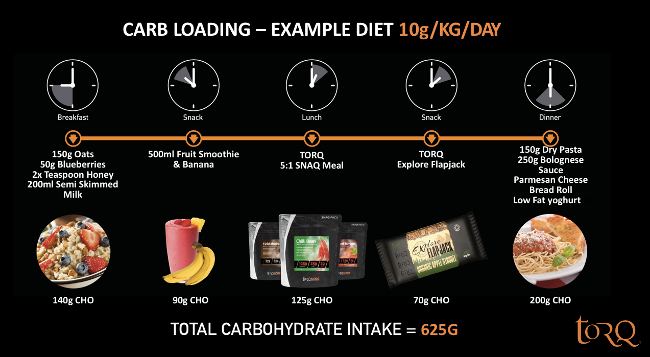

Here’s a brief summary of the carbohydrate loading process:

‘Carbohydrate is stored in limited supply (about 500g/2,000kcals) in the muscles and liver and is a key fuel for high intensity endurance performance. When your stores run out during exercise, you will ‘bonk’ or ‘hit the wall’, a phenomenon that sees any hope of a great performance go to the graveyard! If it’s never happened to you, it’s difficult to describe the experience other than it will probably make you cry! It really is something you will want to avoid at all costs. So to avoid the chances of hitting the wall or bonking during your key event, you should ensure that your starting carbohydrate stores are fully saturated at the start of your event. To do this, consciously increase the amount of carbohydrates you consume within your diet 48-72 hours before your event. As you then reach the 24 hours pre-event, you may wish to become a little more targeted with your carbohydrate consumption and aim to achieve 10-12g of carbohydrate per Kg of bodyweight.’

The diagram above gives an example schedule for a person who weighs around 60Kg. Please note that this is the ‘minimum’ you should be looking to consume. If you weigh 70-80Kg and you want to be hitting 12g of carbohydrate per Kg bodyweight, you’ve got some serious eating to do!

Conclusion

The purpose of tapering is to promote a period of supercompensation or ‘peak in form’ on the day(s) of a big competition or event. The key is to allow adaptation and supercompensation to occur whilst limiting detraining. At TORQ, when we coach, we often talk about 3 scenarios – being tired and fit, fresh and unfit and fresh and fit. Often being tired and fit will give better results than being fresh and unfit, but being fresh and fit is the outcome that’s always going to deliver the best performance. This is what a good taper aims to achieve.

Research suggests that your perfect taper should begin between 8 and 14 days before your chosen event, a longer taper being necessary the higher the training load leading up to the taper. Your training volume should be reduced by between 40-60% and it is critical that your training intensity is maintained. There is very little need to reduce the frequency of your training, but you can reduce this by 80% and alternate training sessions between high intensity interval sessions and sport specific skill sessions to ensure you are priming all of the components required for a perfect race day performance. You should maintain regular consistent protein intake throughout the taper and should aim to increase your carbohydrates intake in the 72 hours leading up to your key event to ensure that your muscle carbohydrate stores are fully replenished. You should complete a high intensity exercise bout 24 hours prior to your event to prime your muscles and neural system for action too.

Other articles in this series include:

Periodisation & Peaking 1: The Off Season

Periodisation & Peaking 2: Planning Your Training

If you have any questions about this article or any other subject, please don’t hesitate in contacting us at enquiries@torqfitness.co.uk or phone 0344 332 0852. Please note that we also have a Fitness Consultancy if you would like to discuss any of the areas of this article in deeper detail. Click HERE for further information on our services.

References

Mujika, I.N.I.G.O., Goya, A.L.F.R.E.D.O., Padilla, S.A.B.I.N.O., Grijalba, A., Gorostiaga, E.S.T.E.B.A.N. and Ibanez, J.A.V.I.E.R., 2000. Physiological responses to a 6-d taper in middle-distance runners: influence of training intensity and volume. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 32(2), pp.511-517.

Mujika, I. and Padilla, S., 2003. Scientific bases for precompetition tapering strategies. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 35(7), pp.1182-1187.

Bosquet, L., Montpetit, J., Arvisais, D. and Mujika, I., 2007. Effects of tapering on performance: a meta-analysis. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 39(8), pp.1358-1365.

Henderson, Z.J., 2016. Peaking and tapering in endurance athletes: a review. The Post, 1(1).

Rønnestad, B.R., Hansen, J., Vegge, G. and Mujika, I., 2017. Short-term performance peaking in an elite cross-country mountain biker. Journal of sports sciences, 35(14), pp.1392-1395.

Hickson, R.C., Foster, C., Pollock, M.L., Galassi, T.M. and Rich, S., 1985. Reduced training intensities and loss of aerobic power, endurance, and cardiac growth. Journal of Applied Physiology, 58(2), pp.492-499.

Coyle, E.F., Hemmert, M.K. and Coggan, A.R., 1986. Effects of detraining on cardiovascular responses to exercise: role of blood volume. Journal of Applied Physiology, 60(1), pp.95-99.