We provide you with the tools and education needed to plan your training so that you peak for your key events next year – a concept known in the world of Sports Science as ‘Periodisation & Peaking.’

In the first article of this 3-part series, we discussed the importance of having an off season at the end of your competitive year to help fully recharge your batteries, giving both your physiology and psychology a break from the rigours of competition and focussed training. The aim of this second article is to get you going again and help you to build a structure for your training that will firstly ease you back into disciplined exercise again and secondly develop the fitness and performance you will need to perform at your best next season.

What Is Training Periodisation?

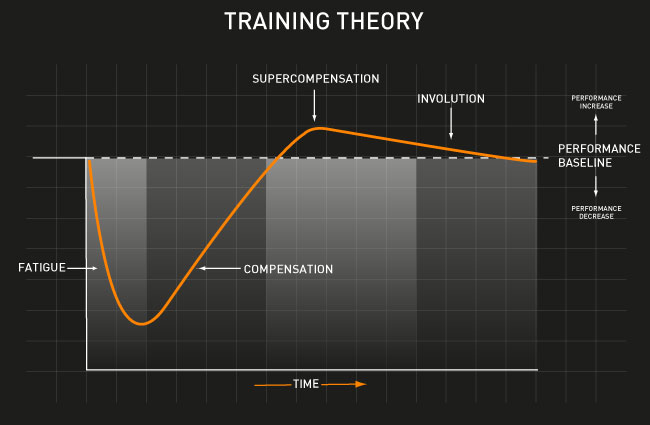

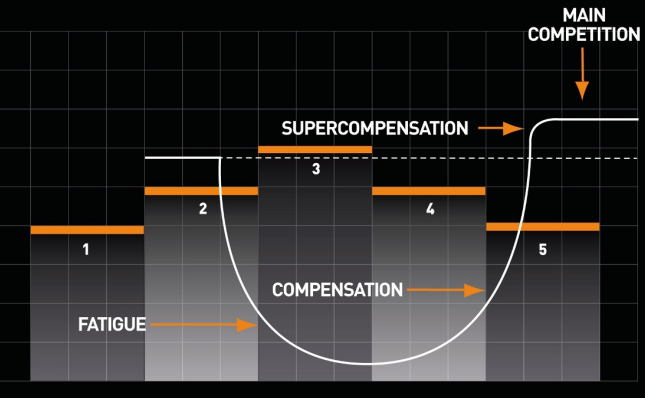

Training periodisation is probably best described as ‘the art of perfect planning.’ It describes the art of breaking down a significant long-term goal into smaller, more manageable chunks. This process maximises motivation and allows you to target specific training requirements based on the demands and timing of key future events. A periodised plan will also allow you to plan periods of focused recovery, which are usually scheduled at the end of a hard training block, or within a taper phase which would typically precede a race week. Either way, this period of planned down-time will ensure that you are fully recovered, fresh and fully adapted from the rigours of hard training. The result being an elevated state of performance and freshness referred to in the world of Sports Science as ‘Supercompensation.’

The principle being that fatigue is necessary to stimulate adaptation, but recovery is essential to allow compensation, resulting in an increase in fitness/performance.

By following higher load training periods with easier recovery/rest weeks, you also create a motivation gradient. Understanding that there is some light at the end of the tunnel will drive you to see that tough period of training through, knowing that you will reap the rewards at the end of it with a period of lower workload, along with less pressure and lower self-expectations.

Understanding The Demands Of Your Sport

Before you can start to build your periodised plan, it is important that you take some time to understand the demands of the event that you are working towards. Your discipline may have very different different physiological requirements to someone else’s, so one plan will certainly not fit all.

For example, an ultra-endurance athlete will require a developed aerobic foundation to support the extended duration of the event, maximising oxygen delivery and efficiency. A developed aerobic foundation will also stimulate fatigue resistance thus improving exercise economy at a sustainable pace/power.

On the other hand, while a 10-mile Time Trial specialist may also benefit, from a large aerobic capacity, there is also a need to work above this threshold and start to utilise the anaerobic energy system, specifically the lactic acid energy system to improve their maximum sustainable power, otherwise known as anaerobic threshold.

And then there’s the Road or Criterium racer who needs to develop extremely strong bursts of power, tapping into an energy system called the phosphocreatine system.

All of these athletes would need to approach their periodised plan differently, yet the overall principles of periodisation remain the same. Although we don’t have time to cover the specifics of each of these scenarios in this article, we will do our best to set you on the right path and if you would like to discuss your particular situation in more detail, you could always book in with our Fitness Consultancy.

The Art Of Working Backwards

As you look to build your training plan, it may seem logical to start at today and begin planning your training sessions as you move forwards towards your season or major event. If you choose to work in this manner, the implementation of the training becomes the main focus and your training availability seems abundant. However, as you start to work through the plan, you may start to realise that you have overlooked the few days you need to be away for work, a family birthday event that was forgotten about and the evening you are needed to look after the children, all of which reduces your training availability. Not only does this result in the potential to miss sessions, but also generates a disruptive psychological state as you aim to cram your training in around these unscheduled commitments.

This is where the rewards of planning backwards from your key event offers up a true perspective of your available training time. As you work backwards you should consider all aspects of your calendar and daily time availability to develop a true understanding of your training availability. Working backwards also ensures that you schedule the correct amount of taper (recovery) leading up to significant events and that holidays and unavoidable time away from training can be worked around lower load training weeks. It also ensures that you build in adequate recovery units and that the training you set yourself is progressive, yet realistic and achievable.

This is your first step into the world of periodisation.

Training Phases

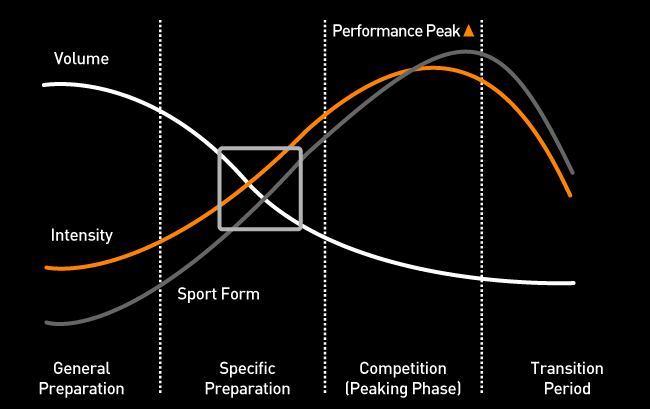

Now that you have a clear understanding of the key demands of your event and your available training time, it is time to start building your training overview. This overview should focus on the bigger picture rather than fine detail of how you are going to prepare yourself for a key event or events. In the first article in this series we discussed one of the training phases in detail – the transitional phase, more generally known as the off-season. However, this is just one of the phases used in the annual planning of a training programme. The full list of phases are:

- General Preparation Phase

- Specific Preparation Phase

- Pre-competition Phase

- Competition Phase

- Transitional Phase (already discussed in this article)

These phases will generally remain in the above order, however the sessions and goals will differ within these phases based on the requirements of your target event(s) or race(s).

General Preparation Phase: The general preparation phase is often considered the period where you ‘train yourself for the training to come’ or the ‘start before the start’. This phase will normally last between 8-12 weeks. Here, you are developing the foundations upon which the event specific training will be built. For many endurance athletes, this typically involves developing a strong aerobic base with progressively larger training volumes, but at a relatively light exercise intensity.

A strong aerobic engine takes a while to build and the more power you can generate via this energy system, the more economical you will be and the less work the anaerobic system will need to do to support performance. Or another way of looking at it is that a strong anaerobic system further down the line (developed during the preparation phase) will combine with your aerobic engine to deliver a higher overall power output and therefore optimal performance. A strong aerobic base will also help the body to recover from intense anaerobic efforts.

This phase may also be a good time to introduce some gym work, which will focus on strength, mobility and the correction of poor movement patterns which will help to protect you from injury as you start to introduce some intensity work later on. Remember that any training phase is all about preparing yourself for the next step and so it’s vital that you do not completely rule out high intensity sessions, especially if top-end power and sprinting ability is an important performance goal for you. By incorporating 1 or 2 intensity sessions a week into your plan, you will ensure that your anaerobic system doesn’t entirely regress, because it will take quite some time to recall it further down the line if you neglect it entirely.

Specific Preparation Phase: As we transition away from the general preparation phase, the specific preparation phase is all about tailoring the training efforts to intervals and sessions that will mimic that of the demands of the target event(s) or race(s). The duration of this phase is typically a little shorter than the general prep phase lasting between 6 and 10 weeks. This is possibly one of the only points in the training phase where both volume and intensity are trained in relatively equal measure (see the intersection between volume and intensity below), however the absolute volume would be less than that completed within the general preparation phase.

As we have maintained a little bit of intensity from the general preparation phase, the intensity built into the specific preparation phase does not come as a complete shock and the anaerobic system is primed for development. That doesn’t for a moment suggest however that the inclusion of an anaerobic/speed focus isn’t going to come without pain!

This is a great time to build on your weaknesses and focus on developing areas of performance that detrain at high rates such as neuromuscular power, (low cadence, high power drills if you’re a cyclist for instance) and peak anaerobic power intervals which typically last for 30 seconds to 1 minute 30 seconds. As these components of fitness are vulnerable to detraining over a short period of time it is important to build these intervals closer to the key event(s) or race(s).

As mentioned previously, both volume and intensity may be relatively high during the early phases of specific preparation and so to ensure that you do not exceed the maximal tolerable load and develop Overtraining Syndrome, the implementation of a ‘step loading pattern’ throughout this phase is likely the best option. We will learn more about loading patterns shortly.

Pre-Competition Phase: Not all coaches will implement a pre-competition phase and will simply incorporate this within the later stages of the specific preparation phase so don’t be surprised if this is a training phase that isn’t familiar to you. This period can last between 3 and 6 weeks and is focused on ‘sharpening the knife’ with a focus on absolute intensity and volume only for maintenance with around 1 longer session per week. It may even involve you competing in sacrificial races/events as part of this preparation.

The desired training outcomes within this phase will generally focus on lactate management and clearance sessions, sessions known as ‘threshold sessions’ and VO2max sessions, which maximise the amount of oxygen that can be delivered to the working muscles. VO2 means ‘volume of oxygen’ required by the body, so VO2max sessions are pretty hard. These sessions look to accumulate between 10 and 20 minutes of ‘time in zone’ (the amount of time you are working within your VO2max power or heart rate range). The interval duration will last commonly between 1 minute 30 seconds and 5 minutes, with between 50% and 100% of the interval time being used as a low intensity recovery period before the next interval starts. If high power sprinting is a requirement for your discipline, phosphocreatine intervals will be introduced – maximal power intervals of no longer than 15 seconds, with a long 5-minute recovery interval between each.

Competition Phase: After months of preparation and working through the various phases, the time to race is now upon you. The competition phase would normally last 1 – 3 weeks if you are planning for a single event, however if you have a filled racing season, this phase may be longer as you aim to maximise your freshness for a number of key events which are close together, i.e. 2 – 3 weeks apart totalling 4 – 6 weeks. In the lead up to the competition phase, the previous training was ultimately responsible for developing fitness without worrying too much about form. Fitness is the long-term accumulation of the training and if the training has been gradually progressive you should see an increase in fitness. With fitness comes fatigue and as we have already discussed (and the Training Theory diagram above illustrated), in order to become fitter, we must stress the body beyond its comfort zone, disrupting the homeostasis which invariably generates fatigue.

This is where the planning of the competition period becomes critical. The aim of this short phase is to reduce the training volume, lowering residual fatigue and bringing form to the forefront in time for the key event(s), before fitness starts to drop off. Leaving this phase too close to a race will result in you still carrying some fatigue and you will not perform optimally. Starting this taper too early will lead to a drop off in fitness and your form will move beyond its peak. Timing is key and we will discuss this in more detail in the next article where we talk specifically about peaking, so stay tuned!

Although this may seem like an awful lot of work for a few weeks of form, you can still have a long and successful season after peaking for a short period, but you will need to go back to building up your fitness again by working through some shortened versions of the phases above. You can still compete whilst training to build fitness back, but the fatigue generated from the training will prevent you from having your best form. Accepting that you simply can’t have your best form for the entire race season is key to understanding how periodisation works. It gives you your best performance at the key events you choose to target.

Training Cycles

In order to ensure the successful implementation of the phases discussed above, you will need to drill down into the detail and understand how to specifically structure each phase. Building training cycles is the next progressive step within the training planning process. These training cycles can be categorised as Macrocycles, Mesocycles and Microcycles and each will progressively add a greater level of detail to the overall plan. The purpose of these training cycles is to manage training load, progression, recovery and motivation within each phase.

Typically, these cycles are broken down into the following;

Macrocycle – Months (e.g. a training phase)

Mesocycle – Weeks

Microcycle – Days

Once again, as you plan out your training, you should work backwards, starting with the larger Macrocycle. Once you’ve planned out your Macrocycle, drill down further into the Mesocycles and by the time you get to the microcycle stage you will be planning in specific details of the actual training sessions you will be completing.

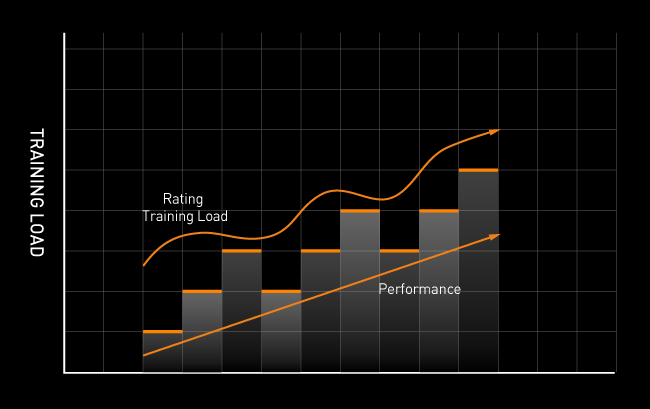

These cycles are governed by what are termed ‘loading patterns’ within the world of periodisation, which structure how much training load you are going to ask of yourself and where/when you’re going to ‘unload’ to give your body a break so that it can recover and compensate. These loading patterns should build in progressively more training load whilst factoring in the recovery units essential for recovery and adaptation (growing your fitness and getting stronger).

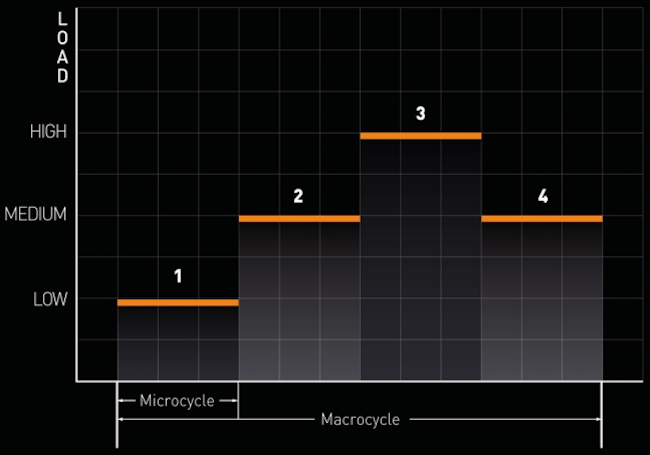

Step Loading Pattern

One way of systematically increasing the training load on your body is via a step loading pattern.

This loading pattern manipulates training load. Training load can be categorised by volume (the number of hours), intensity (how hard the session is), or frequency (how often you train), or a combination of the three. The step loading pattern uses a 3-week build up of progressively harder weeks, followed by a rest week in week 4.

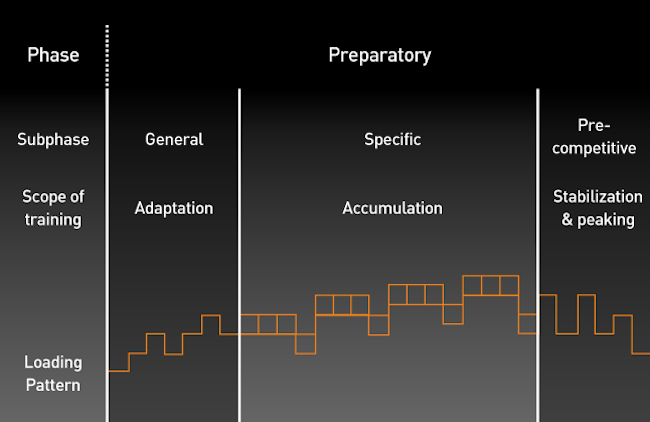

The diagram above shows how a progressive step loading pattern of training can build performance over time by giving the body the stimulus to adapt by creating accumulated fatigue, whilst providing sufficient recovery units to allow improvements in fitness to take place as well as ensuring psychological/motivational recovery in considered.

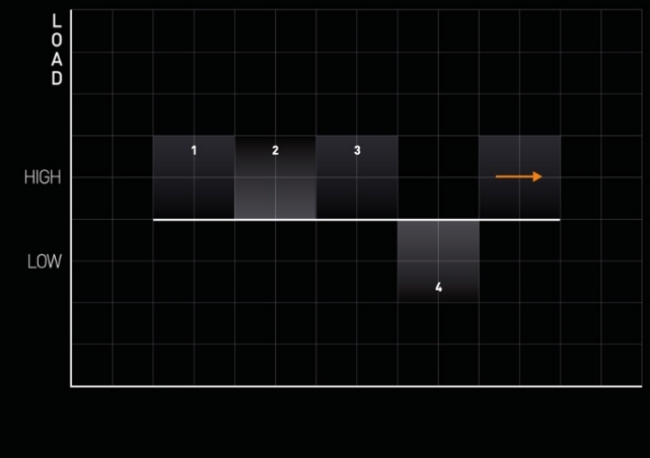

Flat Loading Pattern

Another loading pattern used by athletes is the flat loading pattern, which unlike step loading, training load remains constant over 3 weeks followed by a rest week. The flat loading pattern will rely on you maintaining your maximal tolerable training load for 3 weeks in an attempt to build as much fitness as possible. This loading pattern is typically used by elite athletes who have the significant physiological foundation to tolerate such high physical loads. However, more recently this pattern has also been implemented by amateur/hobby athletes who find themselves restricted by time and want to program in a defined rest week as a reward for a sustained period of high load training.

This pattern becomes logical when available training time may be the most significant restricting factor in performance development. If you have limited time availability, you will want to maximise the amount of training you can get out of that time and a step loading pattern simply doesn’t provide a sufficient training stimulus.

Typically a step loading approach can be worked in with a flat loading model as the diagram above illustrates. What’s significant is that both methods provide loading progression as well as dedicated recovery units to allow for adaptation and physical/psychological recovery.

Nutrition

Nutrition is a huge subject and one that we’re specialists in, but we do risk this rather long article becoming one of our longest ever if we’re not succinct here!

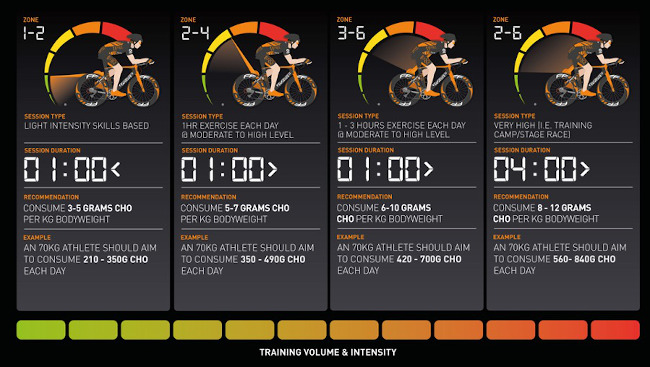

Carbohydrate plays a significant role supporting the ability to complete prolonged exercise or exercise at a high intensity and it is important to understand that as your exercise load (volume, intensity and frequency) increases, dietary carbohydrate demands increase too. Carbohydrates are broken down via the aerobic and anaerobic energy systems and the greater the exercise intensity becomes, the more carbohydrate will be broken down per minute to support the demands for energy production. The graphic below has been developed from years of research examining the carbohydrate requirements of athletes and we have worked hard to formulate simple and effective recommendations to highlight daily targets.

Don’t be fooled, just because a training session may be light, the fact that it lasts for many hours still means you run the risk of ‘hitting the wall’ or ‘bonking’ – the point of which you completely deplete your stores of carbohydrate. This is because both the aerobic and anaerobic energy systems are ALWAYS active (a common misconception) and because of this, some carbohydrate is always being utilised.

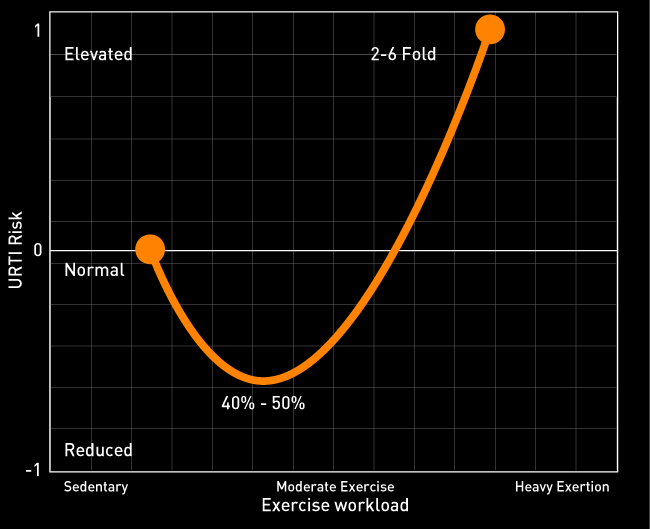

Beyond this, correct fuelling allows for a higher overall workload, so is an essential part of training progression and facilitates the building of higher and higher training loads over the course of your plan. Fuelling with carbohydrate and taking carbohydrate on immediately after training is also proven to protect your immune system. The diagram below indicates how the risk of upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) increases with training load.

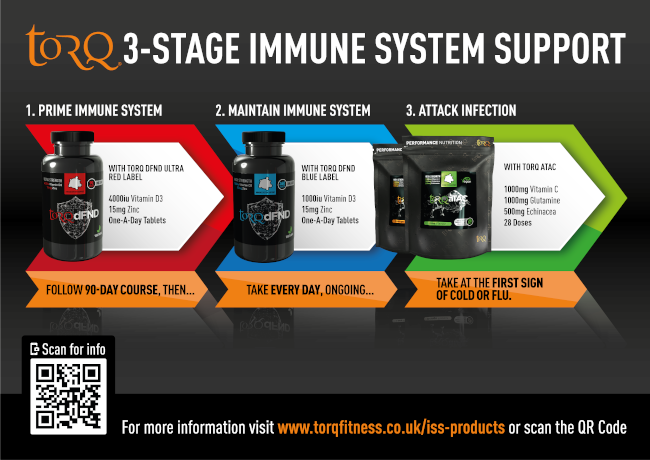

It’s important to understand that a balanced diet containing a wide variety of nutrients is also essential for health and for the normal functioning of the immune system, but strong Vitamin D levels in particular are vital to immune health. 60-80% of the world’s population are deficient in this nutrient, which we explain in our article Vitamin D: Health, Immunity & Performance. Zinc is a nutrient heavily linked to immune health which can be lost from the body through perspiration, so supplementing it may be of specific importance to athletes and physically active people. We discuss Zinc in detail in our article Zinc: Immunity, Health & Performance. It’s for these reasons that we developed TORQ dFND as a daily supplement to ensure these deficiencies are addressed in our customers. We have also developed TORQ aTAC, a product to be taken at the first sign of cold or flu symptoms and the research supports a reduction in the symptoms, severity and duration of colds and flu. Stopping exercise immediately and taking a product like this will ensure the swiftest recovery from infection and will allow you to get back to your training plan quickly. Never train-through illness as getting ill is a sign that you need to back off. With a periodised plan, it’s very easy to schedule in an early rest/compensation week and move things around so you can pick back up with your training once you’ve recovered. The diagram below illustrates how our Immune System Support Range of products work together to help cover all bases.

Finally, let’s also not forget the importance of protein. Protein is a highly valuable nutrient and a whole plethora of information surrounding protein can be found in our article Protein, Performance & 20-25g Protein Recipes. Without well-timed high quality protein feeds, you will not provide the hardware required to recover properly and make your body stronger.

Conclusion

This article was never going to be short, but we hope it provides you with the level of detail you need to start to rationalise your training and piece together a solid and rewarding structure. As alluded to above, with regard to picking up a cold or flu, your periodised plan can be manipulated as and when things come up, so nothing needs to be set in stone, but the more detail of ‘knowns’ you can consider during the initial planning stage, the clearer your path to success will be.

Please bear in mind that TORQ was developed initially as a Fitness Consultancy in 1999 and this kind of topic is our bread and butter, so you may wish to consider booking in for a consultation to learn more? At the same time, if you have any questions about this article or any other subject, please don’t hesitate in contacting us at enquiries@torqfitness.co.uk or phone 0344 332 0852 and we will talk to you freely at no cost to yourselves.

In the final article in the series, which will be launched in our New Year newsletter, we look specifically at how to taper and peak for your chosen event(s).

References

Nieman, D.C. and Wentz, L.M., 2019. The compelling link between physical activity and the body’s defense system. Journal of sport and health science, 8(3), pp.201-217.

Loturco, I. and Nakamura, F.Y., 2016. Training periodisation: an obsolete methodology. Aspetar Sports Medicine Journal, 5(1), pp.110-115.

Owens, D.J., Allison, R. and Close, G.L., 2018. Vitamin D and the athlete: current perspectives and new challenges. Sports medicine, 48(1), pp.3-16.

Owens, D.J., Fraser, W.D. and Close, G.L., 2015. Vitamin D and the athlete: emerging insights. European journal of sport science, 15(1), pp.73-84.

Goutianos, G., 2016. Block periodization training of endurance athletes: a theoretical approach based on molecular biology. Cellular and Molecular Exercise Physiology, 4(2), p.e9.

Kellmann, M., Bertollo, M., Bosquet, L., Brink, M., Coutts, A.J., Duffield, R., Erlacher, D., Halson, S.L., Hecksteden, A., Heidari, J. and Kallus, K.W., 2018. Recovery and performance in sport: consensus statement. International journal of sports physiology and performance, 13(2), pp.240-245.

Esteve-Lanao, J., Foster, C., Seiler, S. and Lucia, A., 2007. Impact of training intensity distribution on performance in endurance athletes. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 21(3), pp.943-949.

Impey, S.G., Hearris, M.A., Hammond, K.M., Bartlett, J.D., Louis, J., Close, G.L. and Morton, J.P., 2018. Fuel for the work required: a theoretical framework for carbohydrate periodization and the glycogen threshold hypothesis. Sports Medicine, 48(5), pp.1031-1048.

Bompa, T.O. and Buzzichelli, C., 2019. Periodization-: theory and methodology of training. Human kinetics.